I remember it like it was yesterday. April 4, 1968—a chilly spring evening in

Austin, Texas where I was attending a Christian university as a freshman. It was also the day Martin Luther King, Jr.

lost his life. Lost it for being

courageous. Lost it for wanting things to change. Lost it for daring to expose

a major flaw in the American dream.

I remember it like it was yesterday. April 4, 1968—a chilly spring evening in

Austin, Texas where I was attending a Christian university as a freshman. It was also the day Martin Luther King, Jr.

lost his life. Lost it for being

courageous. Lost it for wanting things to change. Lost it for daring to expose

a major flaw in the American dream.

You see, his dream was different. He actually believed what

our forefathers had written almost two centuries before was true. All are created equal. All persons—every living, breathing

soul. And at his core, Dr. King knew that

the words to an old familiar hymn were also true:

Jesus loves the little children

All

the children of the world

Red and yellow, black and white,

they

are precious in His sight

Jesus loves the little

children of the world

To Martin’s enemies, the only problem with his thinking was

that Jesus didn’t love them equally.

Or maybe they were content to think “We ain’t Jesus.” Whatever their reason, he

died that day for the crime of wanting a different reality, a new way of

living, an American dream focused more on life and liberty that merely the

pursuit of (one’s own) happiness.

And as much as I deplore this fact, do you know what my

first reaction was to this man’s death, tucked safely, as I was, in the

confines of that small religious institution?

“WHAT A RELIEF. Thank God someone killed that ‘movement’. Now maybe we

can get back to some normalcy.” Oh,

don’t get me wrong. I would never

applaud someone’s cold-blooded murder, in and of itself. But if one has do die to allow the rest of us

to live in relative peace, then so be it.

I was ignorant. I was a bigot in sheep’s clothing. But I was not alone.

Dr. King himself knew all too well that he was swimming upstream, going against the grain,

perhaps fighting a losing battle. Pick your metaphor, but perhaps the most

painful resistance came from his brothers in the clergy, some of whom urged him

to stop upsetting the apple cart. Many, perhaps in their own weariness, had

adopted a “go along to get along” philosophy long ago. Five years prior to his death, Martin wrote

these words from a Birmingham jail to this very fraternity:

“I came across your

recent statement calling my present activities "unwise and untimely."

Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. Since I feel that

you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set

forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient

and reasonable terms.

“… I am in Birmingham

because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left

their villages and carried their "thus saith the Lord" far beyond the

boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village

of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the

Greco Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my

own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for

aid.

“Moreover, I am

cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit

idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham.

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an

inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever

affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live

with the narrow, provincial "outside agitator" idea. Anyone who lives

inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within

its bounds.”

How profound were his insights, not only for the issues of

his day, but for what we, as Americans, face today. Martin Luther King, like

all true followers of Christ, sought to be an extremist for love, for justice,

and for peace. His faith, propelled by

the saving grace of Christ in his life, would not allow him to stand idly by as

others suffered at the hand of the other extremists—those promoting ignorance

and hate, separation and conformity.

Today, we face a similar challenge. While the presenting

issue for Dr. King was the national cancer of racism, his fundamental issue was the tyranny of lovelessness. If King were alive today, I don’t think he would be

limiting his marches to matters of race.

True, racism exists in many, if subtler, forms today, but lovelessness also manifests itself in

our public discourse on topics

ranging from political preferences to individual rights, religion, and community

values. It is exposed in our growing

inability to disagree with one another agreeably.

And at its ugliest, it has reared its head in the form of Islamic extremism, an

ideology which seeks to annihilate every person and belief system counter to

its own.

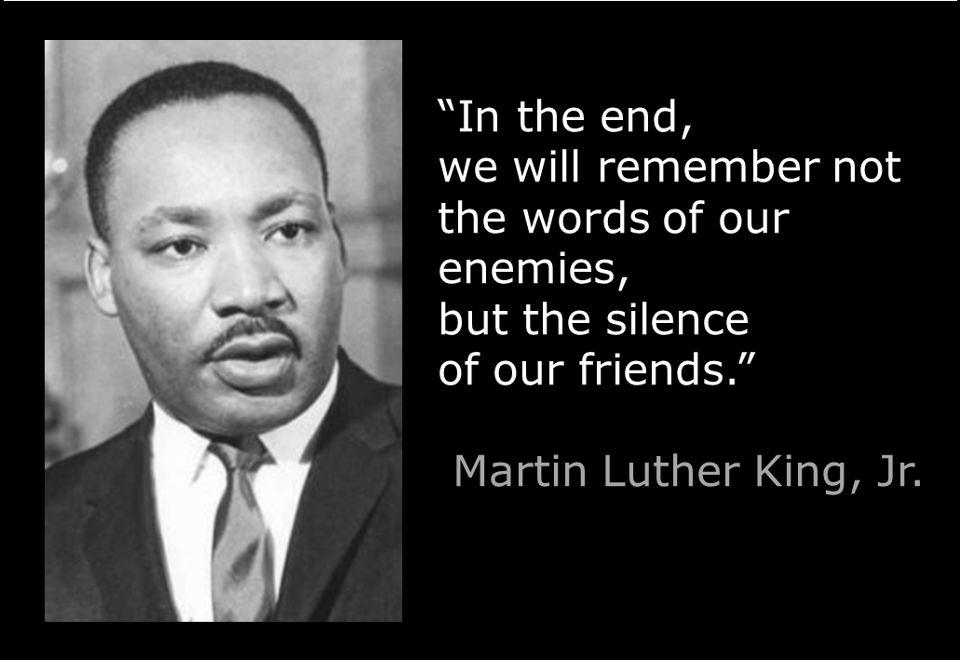

To all of this, I believe Martin would say, rise up,

Church! Rise up, people of God. Oppose injustice at every level, whether it

affects you directly or not. Don’t let

your silence be deafening. As Edmund

Burke once wrote, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good

[people] to do nothing.

My original title for this article was “Confessions of a former racist.” As I examine my heart each day, reacting to

the struggles of people unlike me

culturally, ethnically or otherwise, I realize I am still a work in

progress. But what I do know is that I

am changing. Christ is changing me. And

today, I don’t see change in itself

as a threatening thing. It’s what we are

becoming that really matters. But it starts with a dream.

tad

No comments:

Post a Comment